Trusting God in Dark Days: The Example of Ebed-melech the Ethiopian Eunuch

Image by Shalom Melaku

“I will surely save you, and you shall not fall by the sword, but you shall have your life as a prize of war, because you have put your trust in me, declares the LORD.”

Over the last few years I have grown to increasingly appreciate those minor biblical characters who come on stage for a few verses and then disappear from view, never to grace the Bible’s pages again. People such as the Hebrew midwives, or Simeon and Anna, or the “certain poor widow” who gave much though she had so little.

It is often to such seemingly insignificant, little people that God directs our attention when he wants us to learn what it means to live faithfully in dark days. People like Ebed-melech the Ethiopian, who makes a cameo appearance in Jeremiah 38:7-12, receives a prophetic word of assurance in Jeremiah 38:15-18, and then is never mentioned again.

Ebed-melech Servant of the King

Ebed-melech is the Hebrew for “servant (ebed) of the king (melech)”. It seems that we don’t know his real name, and that being of no real significance or importance—perhaps he was a runaway slave or captive of war—he was pressed into service in Judah’s royal household and named according to his function. All we know is that he was an African (a “Cushite”, typically translated “Ethiopian”) and eunuch. Being a eunuch he was excluded from the assembly of the Lord (Deuteronomy 23:1).

In other words, he was a cultural, racial, and religious outsider.

Ebed-melech Saviour of Jeremiah

At the time, Judah was ruled by Zedekiah, who was the puppet appointment of Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon. Whereas his predecessor Jehoiakim was an ungodly, wicked ruler, Zedekiah was a pathetic, spineless figure who made a pretence of faith but ultimately always feared men more than God. He sought both the prayers (37:3) and prophecies (21:1-2; 37:17) of Jeremiah, but refused to heed God’s word and treated Jeremiah with cold indifference.

And so poor Jeremiah found himself at the whim of Zedekiah’s vacillating judgment. One moment Jeremiah is accused of desertion and imprisoned by state officials in a home turned dungeon (37:11-16). The next, Zedekiah promotes him to house arrest because he wants Jeremiah to provide a divine blessing on his unbelief (37:16-21). Then some court big wigs accuse Jeremiah of disloyalty for continuing to advise surrender to Babylon, and Zedekiah—who claims impotency to stop them—allows them to throw Jeremiah into a cistern, where he sinks into the mud at the bottom and faces certain death (38:1-6).

At which point Ebed-melech, the low-ranking court servant from Africa, steps forward.

He goes out from the palace to meet Zedekiah while the king is “sitting in the Benjamin Gate” (38:7), where he would have been adjudicating legal cases in accordance with God’s covenant law (one of the king’s responsibilities in Israel).

Ebed-melech goes up to him and says,

“My lord the king, these men have done evil in all that they did to Jeremiah the prophet by casting him into the cistern, and he will die there of hunger, for there is no bread left in the city.” (38:9)

Note Ebed-melech’s concern. His reference to the “evil” that had been done to Jeremiah, and his approach to Zedekiah at the time when he is making legal judgments, reveals a man driven by a commitment to righteousness and justice. He was also clearly deeply concerned for Jeremiah’s wellbeing, worried that “he will die there of hunger”.

Zedekiah responds by granting Ebed-melech thirty men to assist him in rescuing Jeremiah. (38:10)

It is not clear why Zedekiah gives Ebed-melech so much manpower. Perhaps it is an indication of just how strong and powerful Jeremiah’s enemies in the court were. Or perhaps it was one of those grandiose acts of virtue-signalling that weak, unprincipled leaders are prone to, as if by sending thirty men with Ebed-melech he was signalling just how concerned he was to see justice done.

But the reader already knows that the king has acquiesced in Jeremiah’s fate and that it’s only now, when Zedekiah is making a public show of doing justice and someone is pleading Jeremiah’s case, that he is persuaded to offer help. Grandiose gesture or not, he is clearly more concerned with the appearance of righteousness than righteousness itself.

What happens next is delightful. Ebed-melech makes the most of his insider knowledge of the king’s palace:

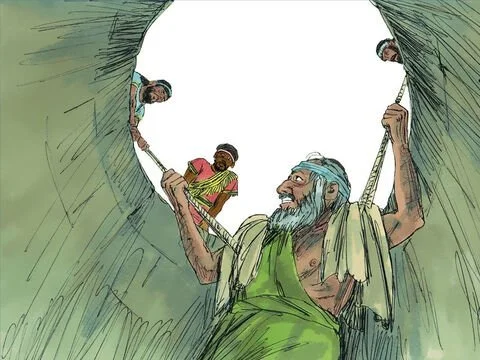

“Ebed-melech took the men with him and went to the house of the king, to a wardrobe in the storehouse, and took from there old rags and worn-out clothes, which he let down to Jeremiah in the cistern by ropes.” (38:11)

Ebed-melech didn’t need to do that, but he is keen to alleviate the pain Jeremiah would feel from having ropes digging deep into his arms as he is lifted out. And so he advises Jeremiah to “put the rags and clothes between your armpits and the ropes.” (38:12)

Jeremiah did so, and the men lifted him out of the cistern.

Image courtesy of FreeBibleimages

Ebed-melech Model of Faith

Ebed-melech’s commitment to see justice done and his compassion for Jeremiah is so noteworthy in God’s eyes, that the Lord sends Jeremiah back to Ebed-melech with a special prophetic word of assurance:

“Thus says the LORD of hosts, the God of Israel: ‘Behold, I will fulfil my words against this city for harm and not for good, and they shall be accomplished before you on that day. But I will deliver you on that day, declares the LORD, and you shall not be given into the hand of the men of whom you are afraid. For I will surely save you, and you shall not fall by the sword, but you shall have your life as a prize of war, because you have put your trust in me, declares the LORD.’” (39:16-18)

Did you notice that? Ebed-melech is commended not for his commitment to justice, his concern for righteousness, his compassion, or his loyalty to God’s prophet Jeremiah, but for his trust in the Lord.

Ebed-melech is an example of what it means to trust God in dark days. We can learn three lessons about true faith from Ebed-melech.

1. The Mark of Faith

It is clear earlier in Jeremiah that to trust in the Lord is to rely on him as the source of one’s security, confidence, and hope:

“Blessed is the one who trusts in the Lord, whose confidence is the Lord.” (Jeremiah 17:7)

The alternative is to rely on human strength and ingenuity:

“Cursed is the one who trusts in man and makes flesh his strength, whose heart turns away from the Lord.” (Jer 17:5)

When we turn from God to people as our source of confidence, we exchange God’s wisdom and strength for that of frail, fallen people. Such pragmatism typically works for a while, but it ends in disaster.

During dark and difficult days, when wicked and unprincipled men lead either the government, or the church, or both, and the enemies of the church are arraigned in power against God’s people (just as the Babylonians were threatening to overrun Jerusalem and finish off the job they had started years earlier), faith in the Lord often seems weak.

What could Ebed-melech possibly gain from sticking his neck out for Jeremiah? Wasn’t Judah’s fate at the hands of the Babylonians already sealed? And wouldn’t Jeremiah’s enemies just seize him and harm him again? And won’t Ebed-Melech now place himself in the firing line as well?

Yes, probably, and maybe. But faith doesn’t reason in accordance with human calculations, or believe the lie that powerful men hold the key to future peace and security.

Faith clings to the Lord alone as its confidence. And the closer it clings, the more the imprint of the Lord’s character and ways is left on the person of faith.

That is why the mark of faith—i.e. the visible evidence that trust in God is present and active in someone’s life—is always conformity to the character of the Lord.

Earlier in Jeremiah, in verses of great importance, God identifies himself as follows:

“The Lord who practices steadfast love, justice, and righteousness in the earth. For in these things I delight.” (Jeremiah 9:24).

God’s “steadfast love” (khesed) is his loyal covenant love that issues in kindness and mercy towards his people.

While the wise man boasts in his wisdom, the mighty man in his might, and the rich man in his riches (Jeremiah 9:23), the person of faith trusts this God: the God of steadfast love, justice, and righteousness. Knowing and trusting such a God is evidenced by delighting in what the Lord delights in himself, namely kindness, mercy, justice, and righteousness.

It is hard to think of a more apt summary of what characterised Ebedmelech’s actions: kindness, righteousness, and justice. By trusting the Lord he became conformed to the character of his Lord.

2. The Man of Faith

In Jeremiah’s day, the result of trusting in the human creature rather than the heavenly creator was that loyalty to the Lord was no longer viewed within the framework of obedience to God’s covenant word, but through the lens of a theo-political nationalism centred around the Temple, its institutions, and its leadership.

Jeremiah was repeatedly judged a traitor because, unlike the sycophantic court prophets of his day, he refused to subscribe to an idolatrous religion that preached a blessing that bypassed the weightier matters of the law, namely justice, mercy, and faithfulness (see Matt 23:23).

At such times, when religion becomes wrapped up in the trappings of ecclesiastical, institutional, or political power and privilege, the only way to relearn what true faith in the Lord looks like is to see it at work in someone like a black, African, eunuch servant called Ebed-melech.

Image courtesy of FreeBibleimages

Why is our attention drawn to Ebed-melech’s little cameo of justice and love? Because God wants to disabuse us of the notion that faith in the Lord has anything to do with our human systems of value, power, and worth, those earthly tribal identities in which we trust and boast. Tribalism is a great enemy of vibrant, saving faith.

Who is the man or woman of faith?

The person who belongs to a particular race? The follower of a particular political party? The adherent of a particular denomination, theological system, or religious leader?

No. It is the person who trusts in the Lord, who leans on him as the God of mercy, justice, and righteousness, and refuses to hope in the wisdom, power, and riches of people and institutions.

Jeremiah has a lot to say about this, the way in which God, through the folly of faith, makes a mockery of the world’s and church’s pretensions to wisdom and power.

For example, as well as drawing our attention to Ebed-melech, he singles out the Rechabites (Jeremiah 35:1-11) as a model of faithfulness. Who, you might ask, are the Rechabites? That’s the point! Just a little-known, nomadic clan in Israel. And Jeremiah wryly observes, through the way he narrates the story, that when Nebuzaradan, the captain of the Babylonian guard, captures Jeremiah, he showed a greater awareness of the stipulations of God’s covenant, and a greater kindness to God’s servant, than a long line of pitiable Judean kings (Jeremiah 40:1-6).

In times of spiritual darkness and national danger, Jeremiah teaches us that we might well be surprised where true faith is to be found.

3. The Majesty of Faith

It’s a great irony that king Zedekiah, whose name means “the Lord is my righteousness” in Hebrew, is taught true covenant righteousness from an African palace servant.

The king was supposed to be the model believer in Israel, the one who imbibed God’s law and led the way in doing justice and righteousness. But Zedekiah doesn’t trust the Lord. Ebed-melech, who does, becomes what the king was supposed to be: a man whose judgment and actions were in lockstep with the law of the Lord.

Ebed-melech acts with kingly majesty and nobility, while Zedekiah, for all his royal power, disgraces his office and betrays his God, giving in to grubby political machinations.

Wendy Widder points out (in an essay entitled “Thematic Correspondences between the Zedekiah Texts of Jeremiah”) that the way Jeremiah 37-38 echoes the themes of Jeremiah 21-24 (no space to go into that here!) presents Ebed-melech as a prefigurement of the righteous branch of Jeremiah 23, the messianic king of righteousness who would one day replace the corrupt line of Davidic kings.

In short, Ebed-melech is a Christ-like figure. He offers us a glimpse ahead of time of that beautiful man from Nazareth, whose zeal for righteousness and justice, and whose heart of mercy and compassion, would make him leave the royal palace of heaven, stand before the judge’s seat, and then go down into the pit of death to lift us out and lift us up to his side.

Which brings us back to the first point about faith, namely that the mark of true faith is that it conforms us to the character of the Lord.

We often say that faith is evidenced by works, and that is true. But faith is evidenced by a particular kind of works, namely works that reflect the image of God’s Son, the merciful, humble king of righteousness.

Those who trust him become like him. Those who don’t won’t. The former is promised salvation: “I will surely save you” (Jeremiah 39:18). The latter finds just how inadequate human strength is when the wrath of the Lord comes.

Share this post: