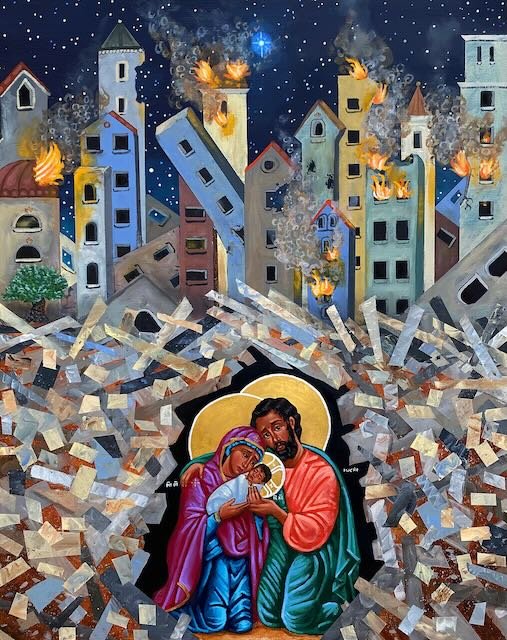

Christ in the Rubble

Art by Kelly Latimore.

“And the Word became flesh, and pitched his tent among us.”

As is often observed, when the apostle John speaks of the eternal Word becoming flesh, and “taking up residence” or “pitching a tent” among us, he is alluding to Israel’s time in the desert, where God once dwelt among his people in the tabernacle, the Tent of Meeting. In their midst, at the heart of their life together, his glory came to dwell.

That allusion, to the tabernacle in the wilderness, helps us grasp the significance of the Word becoming flesh. God in his holiness and his ineffable majesty is, by nature, far removed from us. He is above us and beyond us. And even when he condescended to reveal himself to his people in the past, there was a distance and a hiddenness on God’s part.

But now, in becoming flesh, he has come near in the most familiar, most intimate form possible, subjecting himself to life as a human person, among human people, and for human people.

Where we live—in hardship, conflict, danger, sorrow, and death—he now lives. And how we live—in fleshly weakness—he now lives.

This year, the churches of the occupied West Bank have decided to cancel Christmas festivities. Instead, as an act of solidarity with the suffering people of Gaza, they are commemorating “Christ in the rubble.” The Lutheran Church in Bethlehem decided to change the traditional nativity scene to one of the baby Jesus lying in a manger of rubble and destruction. Munther Isaac, the church’s pastor, sees the gesture not only as an act of solidarity with the suffering people of Gaza, but as a way of highlighting elements of the Christmas story often obscured in the midst of festivities.

In a sermon to his congregation, Isaac says,

“This [Christ under the rubble] is precisely the meaning of Christmas. This year due to the death, destruction, and rubble in our land, this is how we welcome ‘The King of Glory’ … Christmas is the presence of baby Jesus with those who suffer … If Christ were to be born today, he would be born under the rubble. I invite you to see the image of Jesus in every child killed and pulled from under the rubble … Yes, Christmas celebrations are cancelled this year, but Christmas itself is not, and will not be canceled, for our hope cannot be canceled. Jesus’ birth is our hope; Jesus is our hope.”

December 2023, Evangelical Lutheran Christmas Church, Bethlehem. Photo: Munther Isaac.

Isaac and other Palestinian Christian leaders are deliberately highlighting an aspect of the nativity story easily sidelined in the midst of celebration and feasting.

In Matthew’s Gospel, as in John, the birth of Jesus means that God is now with us. He is the promised “Immanuel” (Matt 1:23). And also, as in John, his presence with us now means that he embraces our condition under the curse of sin and death.

John communicates that thought with the one word “flesh.” Matthew communicates it by showing how Jesus recapitulates Israel’s troubled, tragic history of slavery and oppression under foreign powers, first in Egypt, and then later in Babylon.

Like Israel, Jesus is called out of Egypt (Matt 2:13-15). And, just as Jesus spells a new exodus from Egypt, so he inaugurates a new return from the hopeless misery of exile (Matt 2:16-23). He does so by recapitulating in his flesh Israel’s bondage and exile. He takes Israel’s plight to himself. He is born under an oppressive (Roman) occupation. He is from a nothing town where no one of importance lives (Nazareth). And he spent his early years on the run, a displaced person in a foreign land. From infancy, he lives in the shadow of death, with a target on his back.

He was “made like his brothers in every respect” (Heb 2:17). He came to us “in the likeness of sinful flesh” (Rom 8:3), embracing our miserable bondage under Satan (John 12:31; Eph 2:2), that we might be set free.

So, yes, in a very real sense Christ was born in the rubble. In the rubble of this broken world, where the wicked, satanic Herods have their throne, and where their victims cry out in misery for mercy and deliverance.

The Massacre of the Innocents, Tintoretto, 1582

This Advent, wicked Herod-like rulers—Yahya Sinwar and Benjamin Netanyahu and their respective cronies—have inflicted untold misery on thousands of people.

In response, western evangelical leaders were quick to condemn Hamas’ horrific assaults on October 7, and express support for Israel (e.g. here and here). But they then fell silent when Israel began to assault the population of Gaza with first a blockade and then a relentless barrage of indiscriminate bombing, targeting hospitals, mosques, churches, agricultural lands, and journalists in the process.

Still, to my knowledge, they remain silent as Palestinians face death, starvation, and disease.

The Israeli assault has been so cruel that in 10 weeks 62 Palestinian journalists are reported killed, with others arrested, injured, or missing (CPJ report). Most grimly of all, about 10,000 children have so far been killed, a record for daily child deaths in modern warfare.

Sadly, Israel’s brutality has possibly now eclipsed that of Hamas. As such, it is extraordinary that western evangelical leaders, so vocal in their condemnation of Hamas and support of Israel, have fallen silent as innocent Palestinians are slaughtered.

Of course, a double standard is at play here, just as it is with various western political leaders, especially in the USA. Rather problematically (and ironically), several western evangelicals have spoken of the need for moral clarity (e.g. here, here, and here) while being one-eyed in their surveying of the moral landscape. They warn about “bothsidesism”, as if we’re not supposed to apply international law, let alone God’s moral law, to both parties in the conflict.

Heilige Nacht (Geburt Christi) by Albrecht Altdorfer, 1511

By surveying the scene of conflict and choosing sides based on relative virtue, we are obliged to modify our stance if an apparent moral disparity is no longer present, as indeed it most certainly isn’t. Otherwise we simply identify with those with whom we can relate, and relegate the others to, well, other than us. They don’t have our values. We are civilised; they are not. We renounce terrorism; they do not. We fight fair (yea, right!); they do not.

God calls us to remember those who are entrapped as if we were so entrapped with them, since we share the same body (Heb 13:3). As Christians, our solidarity with the afflicted transcends all political alliances, as well as all national or racial allegiances. If we distance ourselves from those whose plight Christ has in the weakness of his flesh made his own, then we do not side with him. Rather, we risk parroting the agendas and aping the postures of the worldly powers that God has brought to nothing in Christ (1 Cor 1:28).

As Bonhoeffer says in one of his letters, written at the turn of year 1942-43, reflecting on the horrors of his own present: “The only fruitful relation to other human beings—particularly to the weak among them—is love, that is, the will to enter into and to keep community with them. God did not hold human beings in contempt but became human for their sake.”

Bonhoeffer notes how we fall victim to “our opponents’ chief errors” by joining them in despising the other. He warns us that “nothing of what we despise in another is itself foreign to us.” If we cannot see ourselves both in the misery and destitution of others, and in their violence and hatred, then we do not yet know ourselves. And nor do we really know Christ, who did not hover above the fray, as he had every right to do (for he certainly was morally separate from us) but made our plight his own, reaching down to the very depths of our miseries and hatreds.

Wherever you choose to stand this Christmas on the conflict in the Middle East, know that you are not standing with Christ unless, like him, you humble yourself and dwell alongside him in the rubble of Gaza as well as alongside him in the rubble of Israel’s kibbutzim. “Is God the God of Jews only? Is he not the God of Arabs too? Yes, of Arabs too, since God is one.” (Rom 3:29-30)

Praise God that the one and only Son took on flesh and dwelt among us; among Palestinians this Christmas in the rubble of Gaza, with the thousands of displaced and dying in the land of Jesus’ birth. And also with you and me in the rubble of our own tragedies, hatreds, losses, and shattered dreams.

God came down at Christmas that he might lift us up out of the rubble. And he raised us, at least in part, that we in turn might dwell by his power among the helpless, frightened outcasts of this dark world.

Share this post: